Books are Not "Red Flags"

A response to Dazed's recent article: '10 Books That Are Dating Red Flags', as well as some recent discussions about "White Male Writers".

This last weekend, Dazed published an article: 10 Books That Are Dating Red Flags.

The article featured a list of books that have been used by literary meme culture for years to profile a certain type of reader. Basically, the Dazed list mocked the favourite books of softbois.

What is a softboi? He’s a male stereotype immortalised by the legendary meme page @beam_me_up_softboi, a dude characterised by his “alternativity”, emotional sensitivity, and inflated ego. Of course, there are lots of alternative, emotionally sensitive, and slightly arrogant guys in the world. What distinguishes the softboi, however, is their pervasive, misogyny – a trait they try to hide, but invariably reveal as they bookend their literary chat-up lines with a request for tit pics. More and more nowadays there are some who intersect with more overtly misogynist movements - softbois putting the “alt” in “alt-right”.

Mocking softbois has become a cultural pastime. Their desperation to be seen as enlightened makes their inevitable slip-ups irresistible entertainment. But while mocking men’s literary tastes can be fun, it also creates a problem: shaming certain books can discourage young men from engaging with literature at all.

Before getting started, I should say that, except for Percy Jackson, I have, over the years, read every one of the books featured in the Dazed list. Crucially, however, none of the books in this list have come to define my personality – which is the real red flag the Dazed list implies. To summarise, here are the books the article mentions:

1.) A Clockwork Orange – Anthony Burgess

2.) The Catcher in the Rye – J.D Salinger

3.) The Alchemist – Paolo Coelho

4.) The Subtle Art of Not Giving a Fuck – Mark Manson

5.) Percy Jackson and the Olympians – Rick Riordan

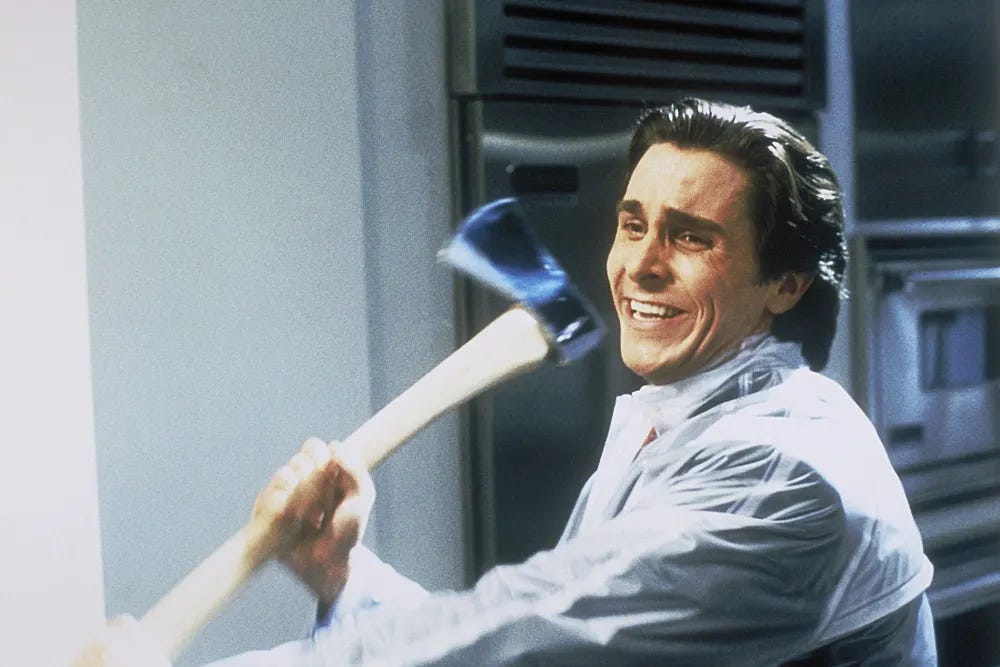

6.) American Psycho – Bret Easton Ellis

7.) Anything by Michel Houellebecq

8.) Lolita – Vladimir Nabokov

9.) All About Love – Bell Hooks

10.) Anything by Dostoyevsky

Now, I’m not going to default to mounting a defence of every book featured in this list. There is enough scholarly work telling you why you should appreciate Michel Houellebecq or Dostoyevsky. I’m also not going to point out the various reasons why somebody might find Holden Caulfield or, shocking though it may be, Humbert Humbert, interesting narrators. After all, the Dazed list is tongue-in-cheek. The problem actually lies with the group it mocks. Young white men are among society’s most sensitive, reactionary, and, crucially, politically motivated individuals - a fact reflected in their support for Donald Trump. When we criticise the literature they might enjoy, we risk creating a new “culture war” flashpoint.

"Just as we are prepared to forget about the crimes of our favourite artist, we are happy to criticise the crimes of somebody else’s.”

Before continuing, I’d like to briefly mention our relationship with music to illustrate a fact, that for some reason, music tastes are not so rigorously policed as literary tastes. I, for example, do not personally love Michael Jackson, given the compelling paedophilia accusations. When I hear that people are big MJ fans, I tend to register a note of unease with the fact they have apparently disregarded these stories. I don’t, however, see their taste as a personality flaw, as the Dazed list implies a taste for these books are. Some people are simply able to ignore the bad qualities about an artist because they are so struck by the good qualities of their art. That isn’t a moral reflection on them. Rather, it’s a testament to the compelling ability of art to seduce us into forgetting our moral convictions. I doubt many of us believe we could sit through an hour-long conversation with a paedophile.1 However, when it comes to listening to an album, reading a book, or watching a movie, there are many instances when we are not only made to forget our disgust, but are happy to.

That said, art is subjective. Therefore, just as we are prepared to forget about the crimes of our favourite artist, we are happy to criticise the crimes of somebody else’s. Dazed’s list recycles a few literary works that have become fashionable to mock. The reason for this is, of course, not for the books themselves, but for the type of people who misinterpret them. There is of course, nothing more disquieting than a gymbro who idolises Patrick Bateman, and Dazed correctly identifies the ways in which these works are routinely misinterpreted. My issue with Dazed’s list, however, is the way it validates jokes made by meme culture to imply a fashionable way to perceive a book when, as well all know, free interpretation is at the heart of our enjoyment of literature.

This cultural policing of books ties into a bigger, thornier debate: the so-called decline of the white male author — and, by extension, the white male reader. Recent months have seen an uptick in discussions about “The Vanishing White Male Author”. An article by Jacob Savage in The Compact approached the issue with a lot of exaggeration. Savage leans so far to the right, he falls off his chair, claiming that through the 2010s “the literary pipeline for white men was effectively shut down.”2 He also claims “the antiseptic legacy of Obama-era MFA programs hangs over this generation” of American writers. Ugh.

Arguing against this, a Substack piece by The Common Reader claimed that the supposed phenomenon of the decline of white male writers was “a mirage, not a cultural crisis” - another claim I disagree with. This claim ignores the elephant (or should I say, the lack of the elephant) in the room.

“A bloke reading American Psycho could, of course, misinterpret it. But there is also the possibility that Ellis’ critique of neoliberalism could smuggle its way in, much like dog medicine smothered in peanut butter makes its way to a puppy’s stomach.”

The debate about young white men as readers and writers currently oscillates between alt-right claims that publishers are refusing white male novelist’s due to prejudice or diversity drives, and left-wing writers, who either stick their head in the sand, or argue that young white men have had their time in the spotlight and should respectfully step aside to allow for more diverse voices. Some writers, such as Alex Skopic, even make the ridiculous claim that everything that could be said about the white male experience was exhausted during the last century. “You’re an up-and-coming White Male Writer… What are you going to write about our current conditions—widening economic inequality, white supremacy creeping into the mainstream, rampant scams and deception—that addresses them better than The Great Gatsby did?”

Seriously!? That book came out one hundred years ago. This is a guff claim – like saying nobody should have bothered writing about young love, or Kings, or bereavement, or booze, or witches, or father-son relationships, or weddings, or anything, after Shakespeare died, in 1616.

Believe it or not, there is a way for left wing people to talk about the decline in white male writers and readers. In fact, it is in our interest to talk about this decline, seeing as it coincides with the rise of right-wing values in men and a growing right-wing discourse that thinks “books are useless.” Don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying Bret Easton Ellis, Houellebecq, or J.D Salinger have been singlehandedly holding back the rise of fascism - far from it. All their books contain misogynistic, racist, and outdated material. That said, I do not think they are the sort of gateway drug to fascism some contemporary Twitter users make them out to be. A bloke reading American Psycho could, of course, misinterpret it. But there is also the possibility that Ellis’ critique of neoliberalism could smuggle its way in, much like dog medicine smothered in peanut butter makes its way to a puppy’s stomach. Crucially – and I think this is the crucial difference – a person who has made the decision to read one of these “red flag” books is likely to pick up another book, maybe one that is not a “red flag”. After that, they may pick up another, followed by another, until, lo and behold, these different books actually teach them something good. That’s how some fiction works: come for the gratuitous depictions of violence, leave with a critical view of policing (thanks, Anthony Burgess). Furthermore, time spent reading a book is time spent not scrolling through alt-right TikToks. If we want to encourage this, we need to abandon the impulse to create a climate of shame toward some popular fictions - however cringe, problematic, or outdated, we might find them.

Men do not read as much as they used to. This is partly because contemporary literary discourse has disowned the most popular books read by men. If you think this is an overstatement, just read Savage’s article. Savage expresses genuine frustration with what he calls “attacks on the “litbro,” and “the mockery of male literary ambition” – no doubt he would see Dazed’s article as such an “attack”. Furthermore, the fact that the Dazed article singles out the tastes of male readers3, without pointing out the potential red flag books read by other genders, contributes to the worldview of some men - that contemporary literary discourse is discriminatory and excludes men. Yes, it may be exhausting to attend to the fragile ego of these blokes, but if we’ve learnt anything over the last decade, it’s that male fragility does not respond well to criticism. If the choice is behind a patriarchal dystopia and the gentle coaxing of sensitive Andrew Tate fans back to the pages of great literature, I think we should all take the time to participate in reactivating discussions about problematic books.

If we want men to think critically, we need to allow them the freedom to make their own mistakes. Mocking men's literary tastes won’t stop misogyny. It might, however, stop them from reading — and that’s a cultural failure we can’t afford.

Or, for that matter: racists, misogynists, or any other horrible character.

This is not true. As a writer just starting out, I can attest to the fact the pipeline is open to promising male writers — we just need to write publishable works.

I actually once dated a girl who thought Lolita was the perfect “romance” novel. A MAJOR red flag. The book itself is great, though.